The Hawksian Method for Screen Scribblers

When I worked with Alex Kurtzman and the late, great Roberto Orci, I watched them do something unusual with their early drafts. Before the action lines, before the scene descriptions, before the translation into screenplay form, they often created a version that was dialogue only.

Actors on the page. Voices in conflict. Rhythm over formatting.

It struck me because I had only heard about this approach before. Howard Hawks built films this way. Scripts began as conversations, spoken aloud, shaped through performance.

Hawks and his stable of brilliant scribes like Ben Hecht and William Faulkner moved their stories with momentum, not outline.

The drafts happened via voice, not just words on a page.

Dialogue was performed, not sculpted. Scenes were discovered through sound, pacing, and rhythm long before ink hit paper.

For us modern scribblers, his OG approach is worthy of a revisit.

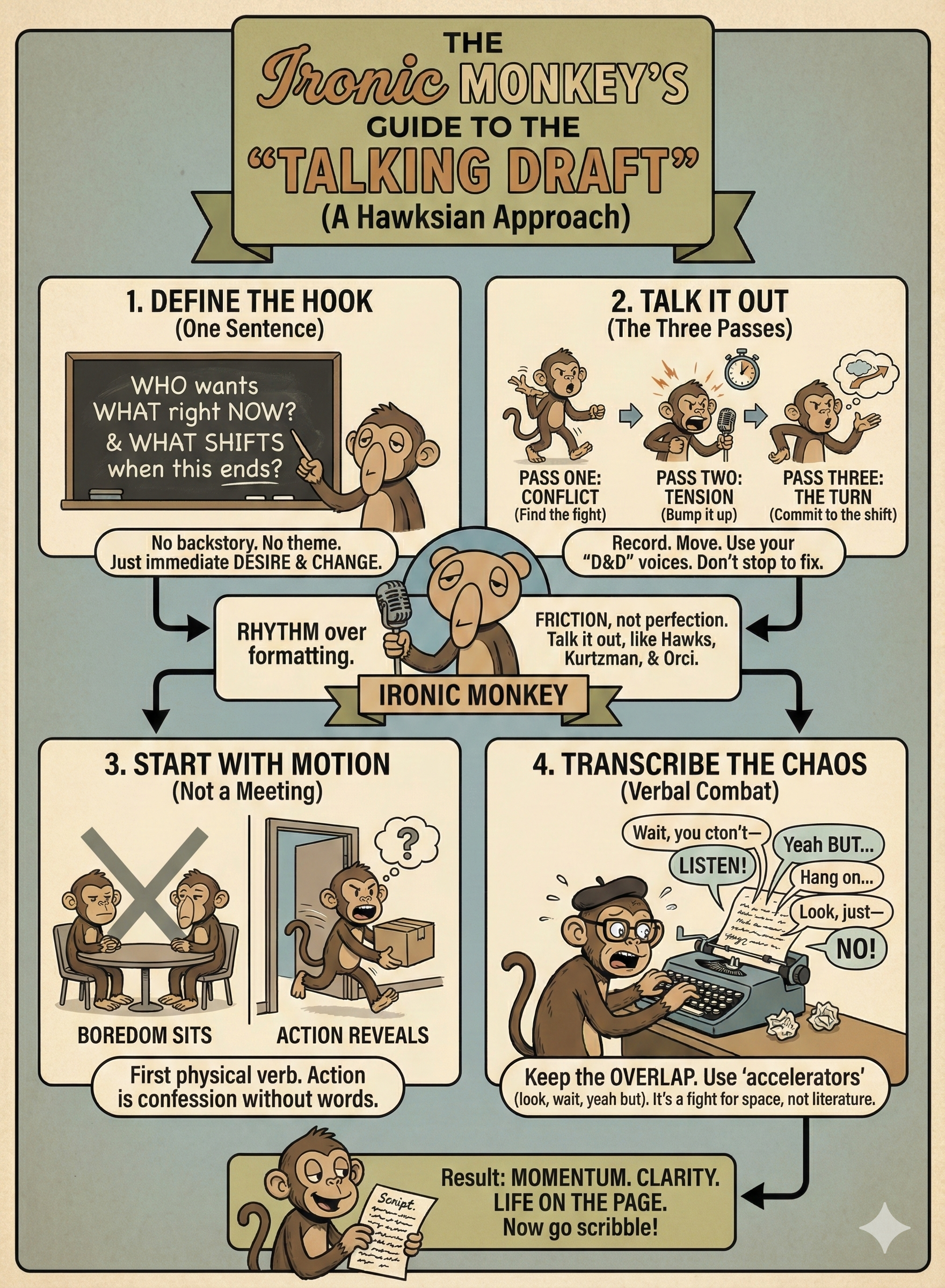

TALK THE SCENE BEFORE YOU TYPE IT

You begin with a single sentence that captures what the scene is supposed to change.

Not backstory.

Not theme.

Not the history of your world.

Just one line that answers, “Who wants what right now and what shifts when this ends?”

Then you record yourself. Stand up. Walk. Pace. Play both characters. You’re not searching for perfect lines. You’re searching for friction.

If you spent time around a D&D table, this part comes naturally. Those years improving characters across a map, switching voices between the paladin and the rogue, reacting without a script — that was your training.

Do this three times without pausing to fix anything.

Pass one finds the conflict.

Pass two bumps up the tension.

Pass three commits to the turn.

Only then transcribe. This isn’t literature. It’s verbal combat.

The object is speed. The goal is rhythm. The win is surprising yourself with choices you’d never find by typing in silence.

OVERLAP CREATES ENERGY ON THE PAGE

Hawks didn’t write pristine dialogue that let every character say their peace in turn. Real conversation rarely pauses politely. It ping pong crowd surfs. Interrupts. Pushes. Landing mid thought.

So when you transcribe, keep that chaotic vibe.

You can use small runway words to allow overlap.

Look, listen, hang on, wait, yeah but.

These aren’t filler. They’re accelerators. Momentum moments. Forging escalating pressure points. They’ll make the audience lean in because they recognize real people fighting for space.

Try for one essential line. A zinger the audience must walk away with. Everything else is texture.

If your cleaned up version feels slower than the recording, you probably scrubbed too hard. Roll up your sleeves and go again.

START WITH MOTION, NOT A MEETING

Hawks believed movement reveals story more than jibber-jabber.

So if you open on two people sitting, the scene sits with them. But if you open on someone entering, leaving, packing, ripping, repairing, hiding, searching, or blocking, the audience leans in to understand why.

Action is a confession without words.

Before finalizing a scene, ask yourself:

What is the first physical verb the camera will see?

If the audience can understand the emotional state of the scene before anyone speaks, you’re on the right track.

CHARACTER AS ENGINE, NOT PLOT

Hawks knew how plot could be a confounding labyrinth, but the audience wouldn’t care if the characters were worth tracking.

The Big Sleep is famous for its confusion, yet it’s a classic because Bogart and Bacall kept generating story via personality. Their decisions kept changing the temperature, forcing momentum.

The plot didn’t drive them. They drove the plot.

Your version of this:

The story moves because a character makes a choice, not because the outline demands a twist.

If a scene ends on a human choice, your audience remains connected. If it ends because the story needs to go somewhere, they’ll detach to the lobby for more malt balls.

THE SOLO WORKFLOW

- One sentence that captures the change. - Three talking draft passes. Record. Don’t rewrite mid stream. - Transcribe the final pass, keep the rough edges.

- Add overlap that reflects human collision.

- Replace early dialogue with physical behavior.

- End the scene with a character choice that drives story forward.

Do this for three scenes and patterns emerge.

Do this for ten and your voice gets sharper.

Do this routinely and the story breathes from the inside out.

SCRIBBLER’S TAKEAWAY

The Howard Hawks Method can be a viable tool for modern scribes. Alex and Bob applied it to rough drafting Transformers, Star Trek, and more. When you speak your story before typing it, you build compelling momentum, narrative clarity, and emotional impact.

Your process becomes less about arranging words and more about capturing life, rhythm, friction, and choice. The page becomes a record of something that happened, not something constructed.

Why not try it on your next scene? Just one. Speak it aloud before you type a word. See what you find and — always be scribbling!

Infographic with typos and whack monkeys courtesy of NanoBanana.